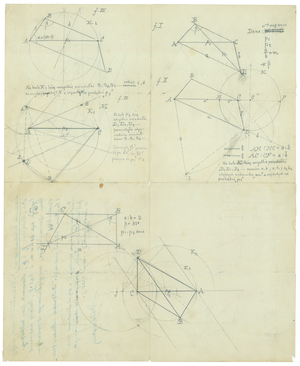

(A) Drogobych. Schulz solves a construction problem from the mathematics textbook by Ignacy Kranz.

(B) In Lviv, Maksymilian Goldstein’s publishing house releases a book Kultura i sztuka ludu żydowskiego na ziemiach polskich (Culture and Art of the Jewish People in Poland), written by Maksymilian Goldstein and Karol Dresdner. The book offers a discussion of Bruno Schulz’s work in fine arts.

(A) Schulz sketched the solution to the problem – some pencil geometric drawings with descriptions – on a 42 by 34.5 cm sheet of paper. On the back of the card, the following information was noted down by Mirosław Krawczyszyn, teacher of mathematics at King Władysław Jagiełło State Secondary School:* “Construction task: draw a trapezoid, knowing the two diagonals p1 and p2, the ratio of both adjacent sides, e.g. a : b = m and the ß angle opposite the parallel side, taking into account the given ratio. / (From Zbiór zadań matematycznych by I. Kranz, Kraków 1920) / The problem was solved and explained by Bruno Schulz, professor at the State Secondary School in Drogobych (in 1935)”.

A teacher of practical classes and drawings at the same school Krawczyszyn worked at, Schulz might have used the “textbook for higher grades of secondary schools,” a popular resource at the time, more than once. An above-average knowledge of geometric rules must have been a useful, natural addition to the subject he taught. In one of his letters to Jerzy Ficowski*, Feivel Schreier* (a former student of Schulz’s) recollects that sometimes in classes with senior lower secondary school students Schulz, indeed, “instead of drawing lessons, run several classes of descriptive geometry, presumably on his own initiative and without the headmasters’ knowledge”. However, was the note with the solution to the task – prepared precisely and almost without mistakes – meant to help Schulz in teaching? It might as well have been a kind of puzzle with no practical application. Edmund Löwenthal*, Schulz’s disciple in the 1920s and a colleague to his nephew Zygmunt Hoffman*, describes Schulz’s special interest in science: “In general, he recommended and valued rationalistic and sceptical thinking, and focused his attention on discoveries in physics, chemistry and biology. Sometimes during Z[ygmunt]’s illness, he entertained us with physical puzzles or interesting mathematical issues; he was quite knowledgeable in this regard”.

Krawczyszyn himself did not remember exactly the circumstances under which he came into the possession of Schulz’s notes. After many years, he accidentally found the double-folded paper between the pages of an old textbook. (jo) (pls)

See also: 17 August 1965*.